Introduction

Most people have heard of Wounded Knee and know it relates somehow to Native Americans without knowing the details. As the cliché states, the devil is in the details, so here is what you probably don’t know but need to about what happened that day in December 1890.

I am posting this in response to the news Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced recently that 20 soldiers involved in what happened at Wounded Knee would keep their military honors. Those soldiers include Mosheim Feaster, who was awarded for “extraordinary gallantry,” Jacob Trautman, who “killed a hostile Indian at close quarters,” and John Gresham, who “voluntarily led a party into a ravine to dislodge Sioux Indians concealed therein.”

Please read what follows, then consider what restoring those honors really says about our country.

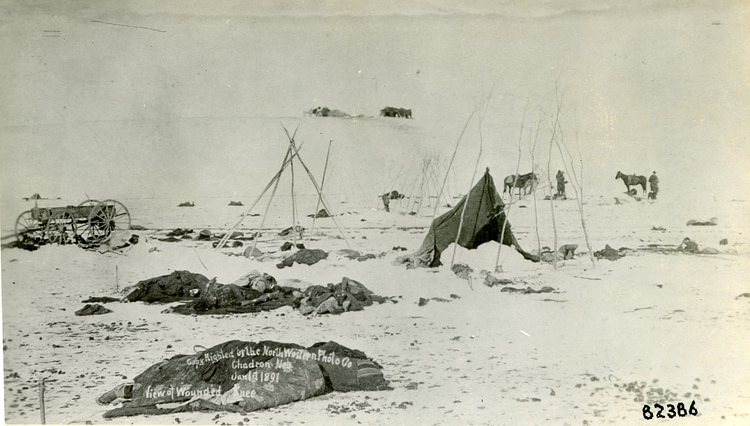

U.S. Army soldiers observing as Lakota dead are buried in a trench. (Library of Congress)

It Wasn’t a Battle

First of all, if you’ve heard it was a battle, you are sadly mistaken. It was a massacre. As many as 300 mostly unarmed men, women, children, and babies were gunned down by the U.S. Army under the command of Colonel James Forsyth. This ended the so-called Indian Wars. The story behind the 1890 massacre is long, deep, and complex, but I will do my best to condense it to the highlights.

Back in 1888 a Northern Paiute from Nevada named Wovoka had a vision during a total eclipse of the Sun. He began sharing what he saw, that the Earth would soon perish, then come alive again in its original, pristine state with lush prairie grass and herds of buffalo, which Native people as well as their dead would inherit for their eternal existence free from suffering.

The conditions to receive this great blessing included living harmoniously and honestly, cleansing themselves often in body, mind and spirit, and shunning the ways of the whites, especially alcohol. They were told not to mourn the dead because they would be resurrected. Prayers, meditation, singing praises to the Great Spirit, and especially dancing, were taught as well as the charge to lay down their weapons and no longer fight, with each other or the white man.

A great gathering with representatives from many tribes occurred at Walker Lake, Nevada, where a Holy Man taught them these principles of peace that Wovoka promoted, along with a specific dance, song, and prayer. It was originally known as the Dance of Peace.

But like most religions, even those of divine origin, original teachings and directives were changed and perverted by those seeking power. In this case, it was Sitting Bull and others, who had not been to Walker Lake to hear its intended purpose, but interpreted the teachings to indicate victory over the white man and restoration of their lands. It’s entire meaning and purpose were twisted and it became known as the Ghost Dance.

While many tribes continued to perform the dance according to its original peaceful intent, some adopted Sitting Bull’s new interpretation as a victory dance. As word reached the U.S. Government, they feared a massive Indian uprising, and in response outlawed the dance in November 1890 and sent out troops to enforce the edict.

Kicking Bear and Short Bull, who had both been at the gathering at Walker Lake, led their followers to the northwest corner of the Pine Ridge Reservation. They invited Sitting Bull, perhaps to explain to him the dance’s original purpose. Before Sitting Bull could leave, however, he was arrested by Indian police. A scuffle resulted in which Sitting Bull was killed as well as seven of his warriors.

Spotted Elk, a.k.a. Big Foot, and his followers were on their way to Pine Ridge as well at the behest of Red Cloud, a proponent of peace, hoping to restore tranquility. General Miles sent the Seventh Cavalry under Major S.M. Whitside to intercept them, finally locating them to the southwest at Porcupine Creek, about 30 miles east of Pine Ridge.

The Indians offered no resistance and were told to set up camp for the night about five miles westward at Wounded Knee Creek. Colonel James Forsyth arrived, took command from Whitside and ordered his guards to place four Hotchkiss guns in position around the camp. There were about 500 soldiers and 350 Indians, 230 of which were women and children (67%).

On the morning of December 29, 1890, the soldiers came into the Indian camp to gather all firearms. While some Indians were aware of the dance’s true nature, some saw it as Sitting Bull had, and wanted to resist. Spotted Elk urged nonviolence, but when one of the soldiers attempted to roughly disarm a deaf Indian by the name of Black Coyote, the rifle discharged.

Other guns immediately echoed the first shot. As the Indians ran for cover, soldiers began firing the Hotchkiss artillery, pursuing some who fled and killing them.

Dick Fool Bull, a child at the time, was an eyewitness. He was traveling with his parents and uncle to join the others at Wounded Knee, but delayed. (The following account was recorded by Richard Erdoes and included in his book American Indian Myths and Legends.)

It was cold and snowing. It wasn’t a happy ride, all the grown-ups were worried. Then the soldiers stopped us. They had big fur coats on, bear coats. They were warm and we were freezing. I remember wishing I had such a coat. They told us to go no further, to stop and make a camp right there. They told the same thing to everybody who came, by foot, or horse, or buggy. So there was a camp, but little to eat and little firewood, and the soldiers made a ring around us and let nobody leave.

Then suddenly there was a strange noise, maybe four, five miles away, like the tearing of a big blanket, the biggest blanket in the world. As soon as he heart it, Old Unc burst into tears. My old ma started to keen as for the dead, and people were running around, weeping, acting crazy.

I asked Old Unc, “Why is everybody crying?”

He said, “They are killing them, they are killing our people over there.”

My father said, “That noise–that’s not the ordinary soldier guns. These are the big wagon guns which tear people to bits–into little pieces!” I could not understand it, but everybody was weeping, and I wept, too…The next day, we passed by there. Old Unc said: “You children might as well see it; look and remember.”

There were dead people all over, mostly women and children, in a ravine…people were frozen, lying there in all kinds of postures, their motion frozen, too. The soldiers, who were stacking up bodies like firewood, did not like us passing by. They told us to leave there, double-quick or else. Old Unc said: ‘We’d better do what they say right now, or we’ll lie there too.’

So we went on toward Pine Ridge, but I had seen. I had seen a dead mother with a dead baby sucking at her breast. The little baby had on a tiny beaded cap with the design of the American flag.

Then, adding insult to injury, starting in 1927 the federal government sponsored the carving of four presidents’ faces on Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills, sacred land to many tribes to this day, for which they fought with everything they had to retain. Furthermore, it was originally given them, then taken back in typical “Indian Giver” fashion when gold was discovered.

There are credible reports that the Holy Man who taught the gathering of Native Americans at Walker Lake was none other than Jesus Christ. Whether or not you choose to believe that is up to you, but clearly the teachings reflected what Jesus taught.

Yet it was supposed “Christians” who slaughtered these innocents and the Pope authorized it through a Bull. Pete Hegseth professes to be a Christian. What Christians have done in the name of religion should be horrifying to any civilized person, from the Inquisition to the Crusades.

I am a white woman who is about as white as you can get. My maternal heritage goes back to Connecticut in the 1600s. My paternal grandfather came from France, my paternal grandmother was French Canadian. Perhaps somewhere in my genealogy someone married a Native American, but as far as I know, that is not the case. I would be proud if it were.

I have done a wealth of research related to writing the Dead Horse Canyon trilogy with my coauthor, Pete Risingsun. It was a startling revelation “how the West was won.” It’s now obvious to me that we stole this land from its original inhabitants. They have been slaughtered, the target of genocide, treaties repeatedly broken, and promises not kept for hundreds of years. In reality, Indigenous peoples were treated better by the English and French than by the U.S. government. The United States has treated people better who attacked us during World War II than they have those from whom they stole this land.

Let that sink in.

The government even initially denied Native American “birthright citizenship” because, even though they had lived here for thousands of years or longer, it was not yet the United States when they were born.

If I were related to any of those 20 men who received “honors” for their part in the Wounded Knee massacre I’d be ashamed to admit it. I am horrified by what they did to say nothing of outraged that someone who claims to be a civilized person would condone such barbaric, heartless actions.

Forsyth was later charged with the killing of innocents, but exonerated. In 1990, Congress declared it a “Tragedy” in a bipartisan resolution. Even Major General Nelson A. Miles, who sent the Seventh Cavalry to intercept those heading for the gathering as noted earlier, condemned the Wounded Knee incident as “the most abominable military blunder and a horrible massacre of women and children.”

And yet, over a century later, our current Secretary of War wants to honor them.

What despicable human being could possibly see anything honorable in what happened that day? In the Post-WW II Nuremberg trials the allies rejected “I was only following orders” as a defense for war crimes. The Nuremberg Charter specifically said that acting under orders was not enough to free you of responsibility — it might only be considered when determining punishment.

Principle IV of the Nuremberg Principles states, “The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him.”

It appears that what is considered immoral action by Nuremberg standards today was okay in 1890 thanks to the Pope.

What is wrong with this picture?

It’s my opinion that Hegseth represents the worst of the white man’s world and epitomizes the “Manifest Destiny” mentality, the very reason that people of color see whites as the enemy.

Have we not learned anything or evolved beyond barbarism in a hundred years?

If this is how war crimes are judged today by the Secretary of War, in full violation of the Nuremberg Principles, then Hegseth should be impeached at least, preferably ousted, for leveling such an insult on people who have suffered enough over the past five hundred years. As far as I’m concerned, the blood of the victims at Wounded Knee is on his hands every bit as much as Forsyth, Miles, and all the others.

If you agree, please comment below, forward this blog, and notify your congressional representatives of your opinion on this matter.

Photo Credits: Library of Congress

References

Waldman, Carl, Atlas of the North American Indian, (c) 2009, Infobase Publishing

Brinkerhoff, Val, The Remnant Awakens, (c) 2018 by the author

Erdoes, Richard and Ortiz, Alfonso, editors, American Indian Myths and Legends, “The Ghost Dance at Wounded Knee” as told by Dick Fool Bull in the 1960s and recorded by Richard Erdoes, (c) 1984