Review of “The Girl in the Middle: A Recovered History of the American West” by Martha Sandweiss

A magnificent must-read for aficionados of the West’s colorful history

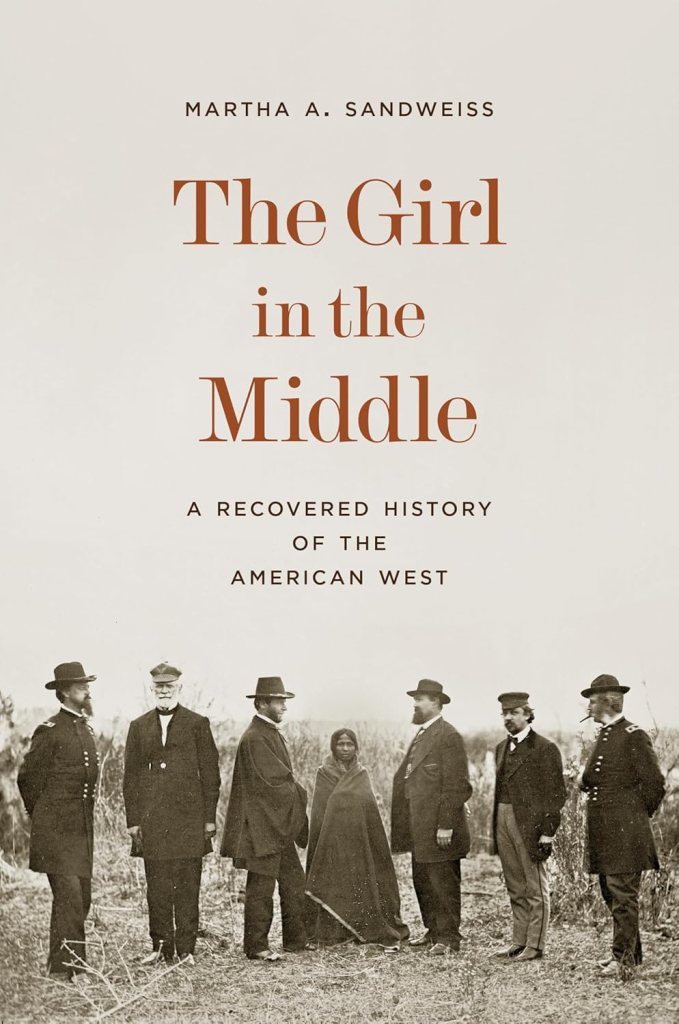

When I saw this book’s haunting cover, I knew I had to find out what was inside. I’m astounded by the wealth of research done by the author and what she uncovered, revealing who and what those six men were as well why they were gathered at that place and time. Sandweiss includes the photographer and even succeeds in identifying the lone Native American girl, whose name was not included in the photo’s caption.

Be aware that every incident included in the text is documented in fifty-seven pages of “Notes.”

Wow.

What an incredible quest! One accomplished through scrutinizing government records of official actions, census records, newspaper articles, wills, land records, and personal interviews with the progeny of those involved.

The men in the photo are General William S. Harney; Senator John B. Henderson; John B. Sanborn; Samuel F. Tappan; Nathaniel G. Taylor; Alfred Howe Terry. The photographer is Alexander Gardner, famous for his documentation of the Civil War as well as portraits of President Abraham Lincoln, General William T. Sherman, and other dignitaries. The girl is Sophie Mousseau.

Looking at it journalistically, let’s use the standard who, what, when, where, and why.

Who: The men are members of the federal Peace Commission.

What: Meet with a multitude of Native American tribes.

When: It’s 1868, the nation still recovering from the Civil War.

Where: Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory

Why: To work out treaties and agreements with the Native Americans

Not a simple task, to be sure.

Within the pages of this amazing tome lie details not found anywhere else about who each of those men were besides soldiers, politicians and activists. Not their public persona: their angels and demons, opinions, political sway, family, and in some cases, criminal records.

Their negotiations with the various tribes is detailed as well.

This is not some dry, impersonal chronology that makes your eyes glaze over like you encountered in high school. It’s an intimate look at not only these men and the circumstances that brought them there, but a glimpse of the true condition the United States (which was still in the process of forming) and the challenges faced by the government.

Besides the challenge of integrating the slaves freed following the Civil War into society, they had troubles galore related to the settlement of the West and working out agreements with the Native Americans. Don’t forget that the nation was also loaded with immigrants, with everyone trying to find their place in the adolescent nation.

You may have heard of the Sand Creek Massacre and Wounded Knee, but what about Blue Water Creek? If you believe like I do that this land was deliberately stolen from its original inhabitants, (who were not considered citizens until 1924 because they were not born in the United States), you will learn even more of the sordid details.

At least some of the Peace Commissioners (obviously not the military members) were actually pretty objective and fair, acknowledging the many gripes the Native Americans had as legitimate. The report even pointed out conflicting values by stating, “If the lands of the white man are taken, civilization justifies him in resisting the invader. Civilization does more than this: it brands him as a coward and slave if he submits to the wrong.” Conversely, “If the savage resists, civilization, with the ten commandments in one hand and the sword in the other, demands his immediate extermination.” While the commissioners didn’t want Indians to disrupt the settlement of the West, they doubted “the purity and genuineness of that civilization which reaches its ends by falsehood and violence, and dispenses blessings that spring from violated rights.” (p. 159)

I was aware that the Black Hills were very much stolen. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which promised the area to the Lakotas in perpetuity, was nullified by the so-called Agreement of 1877 and redrew the boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation to exclude the Black Hills.

Why? To open it up to white settlement and the pursuit of gold while also ending the military defense of Lakota treaty rights.

Originally, that reservation was around sixty million acres. But the 1877 agreement (signed by only about 10% of Lakota men versus the required 75% according to an 1868 treaty), returned most of the Black Hills to the United States. The new reservation was now slightly less than twenty-two million acres, a 63% reduction.

In 1892 the Lakota began demanding compensation. Petitions and protests persisted for roughly 60 years until 1980, when the Supreme Court ruled in their favor, stating that the 1877 federal seizure of the land was done in bad faith without the proper consent from the adult men of the tribe. It awarded the tribe $17.1 million in damages, plus interest from 1877, for a total of roughly $106 million.

That may sound as if the issue is resolved. It’s not. The tribe refuses to take the money, which with accruing interest, would now be around $1.5 billion. Why? Some leaders say it would represent relinquishing their claim to the land–a price too high.

Since then the Seven Council Fires of the Great Sioux Nation has resorted to purchasing parcels of land from private ranchers. The Interior Department now hold that land in trust to be governed by the same laws that govern other trust land in Indian Country.” (p. 273)

Did you know the U.S. Government had a program that accepted “Indian Depredation Claims” from people who had suffered property damage from Indian raids and other incidents? Some of those claims took decades to settle, typical of government programs to this day. Some things never change.

So what about the girl, Sophie Mousseau?

It turns out that Sophie was “in the middle” in another respect as well. Her mother was Yellow Woman, a Oglala Lakota. Her father was Magloire Alexis Mousseau, a French Canadian.

Indeed, Sophie went on to marry and have children with two different white husbands. In censuses and other records it was common for individuals to show up as white in one document and native in another.

This was another situation that arose with its own set of complications, the matter of mixed breed individuals who were often not accepted by either culture. Furthermore, there were Indians who behaved like whites, and whites who behaved like Indians. Some of this came about when reservations were broken up via allotment programs, where many stepped in to grab land, which further reduced the size of reservations.

We think the times we live in now are complicated, but this books demonstrates that the 19th Century was loaded with challenges, some of which we still face today.

If you’re a history buff interested in the growing pains of the American West, many of which still remain as various aches and pains, I cannot recommend this book highly enough. Maybe the detail will be too much for some, but getting to know the people in this iconic photo brings it to life like never before. It was heartening to find out that the Peace Commission did recognize many of the injustices perpetrated against Native People. However, Congress didn’t agree and thus ignored its recommendations as they pleased.

As stated before, Pete Risingsun and I did a lot of research writing the Dead Horse Canyon Saga, but it was nothing compared to what was done to create this amazing book. You can find it on Amazon here.