I tumbled down that particular rabbit hole upon reading, “How to Truly Own your Land: Land Patents” by Ashley Rocks, Kenneth Plaster, and Gwendolyn Morris. More on that later. Since writing the Dead Horse Canyon trilogy with my coauthor, Pete Risingsun, I now filter many issues through what I’ve learned about how “trustworthy” the United States has been regarding Native Americans.

Right. I can hear you laughing already.

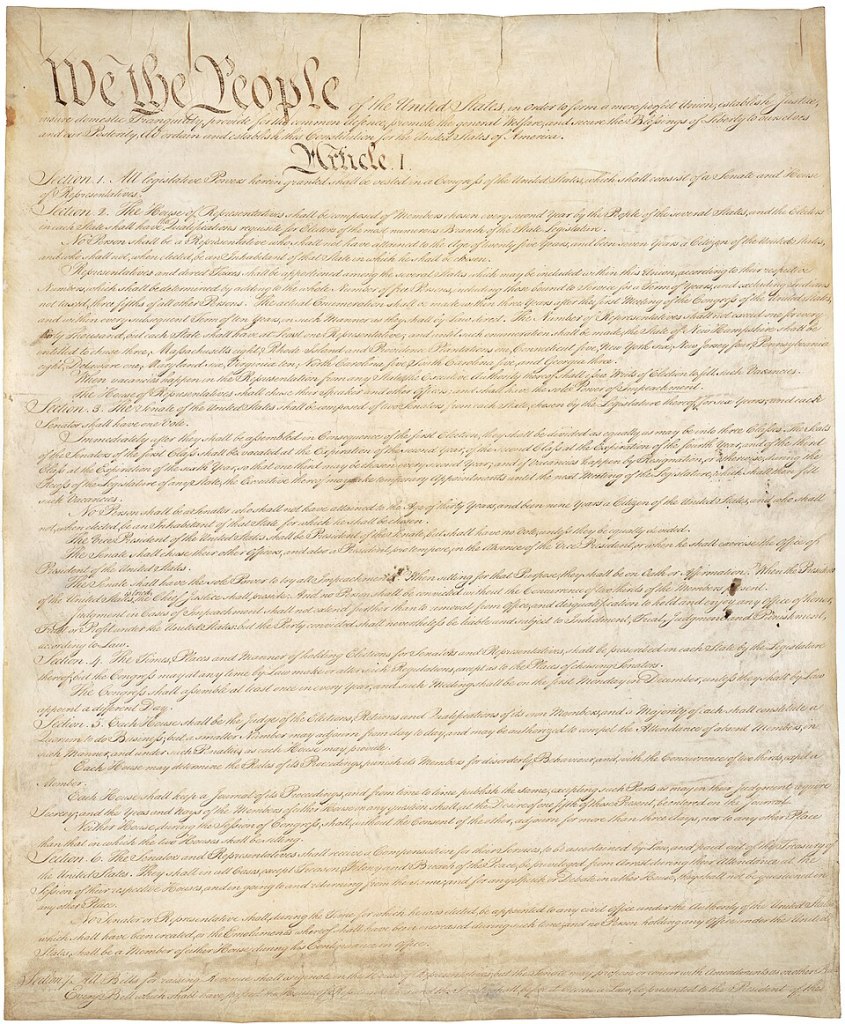

That book about land patents started with Article VI of the U.S. Constitution which states:

“This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”

And that is where I fell down the rabbit hole.

If treaties represent the supreme law of the land, how did Native Americans lose so much of theirs? No Constitutional amendments exist that pertain to Article VI.

So what happened?

Brace yourself for a brief history lesson to illustrate how convoluted that simple question’s answer tends to be. Then we’ll get into how this affects you as a home or property owner.

Consider that the Constitution was ratified September 17, 1787, over a hundred-fifty years after the Pilgrims arrived in 1620. Per Carl Waldman’s “Atlas of the North American Indian,” during the Colonial period, the English, French, and Dutch recognized the sovereignty of Indian nations and negotiated a plethora of treaties. Their intent was mostly to legitimize their own land purchases, claim colonial powers, and establish trade agreements. (p. 236)

Following the American Revolution, it’s easy to guess what happened to those early treaties. Like an incoming hostile landlord, the U.S. Government assumed control with a new set of conditions. Years later, Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution specifically banned states from entering into any treaty or alliance, implying previous ones were of little effect.

From 1781 to 1789 the Articles of Confederation prevailed as the rule of law. The United States’ intent with treaties was typically to legalize the right of conquest.

In a similar manner, Native Americans were not initially granted “birth right citizenship” in spite of Section 1 of the 14th Amendment, ratified in July 1868. Why? Because they were not born in the official United States. Furthermore, reservations were under Indian jurisdiction and therefore were deemed not to qualify.

During the 1850s, numerous treaties were negotiated with Indian tribes, i.e. 52 from 1853 to 1856 alone. Treaties as policy ended with a negotiated agreement between the federal government and the Nez Perce in 1867, the last of some 370 treaties! (Waldman, p. 237) Furthermore, numerous agreements made between tribes and supposed government representatives that failed to be ratified by Congress fell through the cracks while Native Americans signed them in good faith, often not even knowing what they contained.

Is it any wonder Native Americans accused the white man of “speaking with a forked tongue?”

In 1871 an act of Congress officially impeded further treaties. Supposedly, treaty obligations were not invalidated, but Indians were now subject to unilateral laws of Congress and presidential rulings. (Waldeman, p. 237)

In “The Girl in the Middle: A Recovered History of the American West” by Martha Sandweiss she described the meeting the Peace Commission held at Fort Laramie with numerous tribal leaders in 1868. Fast forward to 1873 when Blackfoot (Crow) stated how they were promised a multitude of things that were not actually written in the treaty as described in “Great Speeches by Native Americans.” (pp142-143)

Blackfoot said, “What we say to them, and what they said to us, was “Good.” We said “Yes, yes,” to it; but it is not in the treaty….When we were in council at Laramie we asked whether we might eat the buffalo for a long time. They said yes. That is not in the treaty. We told them we wanted a big country. They said we should have it; and that is not in the treaty. They promised us plenty of goods, and food for forty years–plenty for all the Crows to eat; but that is not in the treaty….”

Of course it wasn’t, since two years before, as stated earlier, Congress impeded further treaties.

Get the picture?

Do you really think the government holds any of its citizens in higher regard than First Nation Americans?

Which brings us to the book that started this tangent.

If you think you own your home or land, think again. While those who came to the New World in the 17th Century did so for freedom and the opportunity to own land versus a feudal system, over the years that has been corrupted like everything else the Founding Fathers intended, reverting back to what they supposedly left behind.

This book is essential reading for anyone who thinks they own their land. You most likely hold an equitable interest title or deed, but do not hold full title to the land. Don’t believe me? Fail to make your mortgage payments or pay your property taxes and see what happens.

If you held what is known as an allodial title, the land would be yours. Period. You would not owe homage to some financial institution or government authority to retain it. It would be yours. Forever.

So why don’t you own your land? This relatively short book of 83 pages describes all the particulars, of which the average person is entirely unaware.

It is possible to obtain a Land Patent, or allodial title, but it involves a complicated process and a lot of research, tracing your property’s ownership history back to its origins as a land grant with an allodial title. While this book is not intended as legal advice, it does give you plenty of information to help you along that convoluted path.

I’m definitely interested in getting an allodial title to my existing land. My property taxes are horrible and nothing would please me more than to be situated to avoid them.

You can get a copy of this eye-opening book on Amazon. It’s a bit pricey for a skinny paperback, but the information it contains could save orders of magnitude more should allodial title be achieved.